Entering Long Thien Shih’s retrospective exhibition, the visitor is greeted by a figure in white hazmat suit, holding out a rainbow-coloured banana. Known for his surreal prints, what is revealing about this 2013 image is how it is no longer surreal, or perhaps reflects the surreal times we live in. Early paintings denote a strong influence by Cheong Soo Pieng, as the artist recognises that his change in approach happened after joining the Wednesday Art Group. Experimentations include sewing a ‘Kampung Nelayan’ scene onto burlap, and illustrating a cubist perspective of tin mine workers in ‘Big Investment’. At 20 years old, Thien Shih studied lithography in Paris, also enrolling at Atelier 17. One wall exhibits his output during this time, the drawings resembling Cheong Laitong with its gaudy colours, but its sinuous lines are evidence of his tutelage under Stanley William Hayter.

|

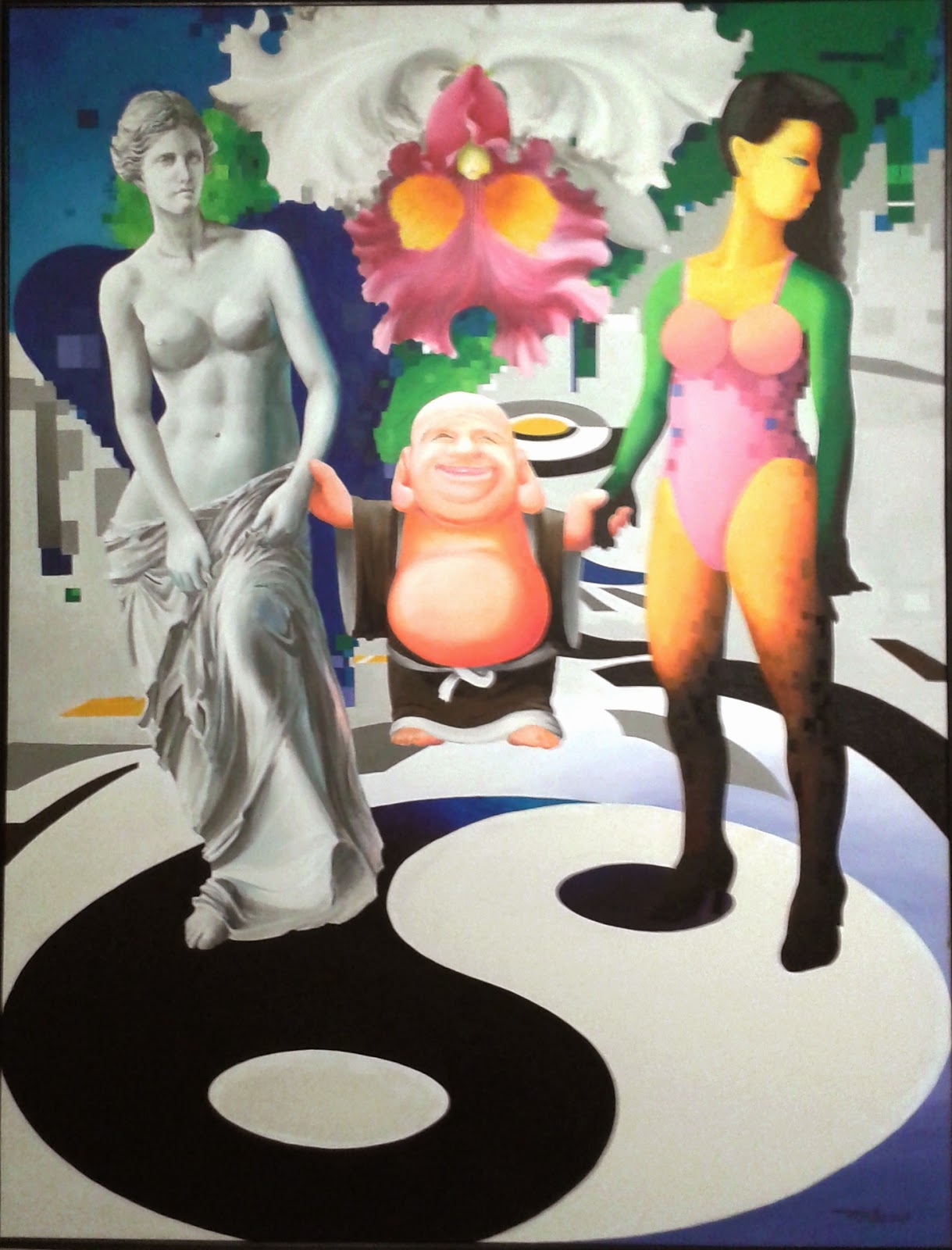

| Let's Joy Together (2009) |

Hung at the end is ‘Susan’s Birthday’, a sexually explicit drawing that leads on to the series of erotic prints produced in the early 1970’s. Body parts take the forms of food and plant, the titillating images capturing personal desires à la Salvador Dali. Minimal juxtapositions in ‘Foot, Hand and Hair’ and ‘Tongue and Egg’ enthral with its simplicity, while the pink tone and overt representations in ‘Chestnut Spikes’ verge towards pornographic content. Visual depth is an apparent concern in works from the later part of that decade; A distant horizon is created via window frames and grounded textures, prefiguring the well-composed prints of Raja Zahabuddin Raja Yaacob. Portmanteau combinations such as a furry hackney carriage and a primitive skeleton, contribute off-kilter elements in Thien Shih’s signature aesthetic.

|

| Chestnut Spikes (1975) |

Less interesting are exhibits from the 1980’s, which employ the birdcage as an ideological symbol. ‘Earth, Water and Air’ depicts one cooped up orchid floating above a pigeon, the repressed flower seemingly a response to the modernism associated to Patrick Ng Kah Onn’s painting of a similar title. As a sexual metaphor, the Cattleya is depicted together with a melted bed, or joined together with floating coconuts in the suggestive ‘Cattlya and Coconuts Airborne’. Delightful etchings hung in this section suggest the loss of natural habitats, such as ‘Run Tree Run’ and ‘Three And A Half Candle’. Another highlight is ‘Kuala Lumpur Art Festival’, which fascinating design includes propped-up facades of an iconic building, a ribbon of patriotic colours, and a red lantern amalgamated into a Mughal-style mosque. Tourism promotional posters have seen better times.

|

| Kuala Lumpur Art Festival (1985) |

A 1967 study depicts blurred lines created from ink wash and roller, which effect is utilised to great result for expressing loss of culture. Traditional objects are distorted in etchings ‘Where Are We?’ and ‘Head Dress of Borneo’, while a spectral fire consumes a living artefact in ‘Borneo Anthropoloque (Call From The Wild)’. Thien Shih’s paintings are equally powerful in his social commentary, by recognising what is visually familiar to the urban audience – tribal dance scenes are distorted by poor television transmission (‘Faulty Image’) or pixelated images (‘Dissolved By Progress’). Works from the past seven years continue to address habitat issues and the cost of progress. Utilising the CMYK model for his colour palette, surreal paintings project a strong artificiality, although its relatively large size makes it less attractive.

|

| Where Are We? (1989) |

Hasnul J Saidon’s interpretation of the superb ‘Bar Coded Man’ is on point – “(d)engan memetik dan mengolah-semula karya Leonardo da Vinci secara digital seperti robot (Leonardo meletakkan tubuh manusia sebagai sukatan untuk segala benda), Abang Long seakan menyindir bagaimana manusia kini disukat menerusi nilai konsumsi atau daya belinya.” By composing an ink drawing from newsprint, capturing and re-printing it, the additive modes of reproduction highlight the ethical issues about replication, visual or not. Exiting this wonderful retrospective of a progressive modern-era artist, curator Tan Sei Hon leaves the visitor with an incisive quote, “(h)is grasp of the visual language and mastery of the elements of art, delivered in wry humour sets him apart in a scene that still lingers in nostalgia and parochialism, that mistakes dour solemnity as a sign of intellectuality.”