What makes a holy site, holy? Looking at digital prints of 130-years old photographs taken at Makka al-Mukarrama and al-Madina al-Munawwara, it is difficult to reach a visual conclusion. As described in the catalogue preface, these two locations “…are specifically safeguarded by the Islamic jurisprudence and considered to be “harem” and are called “Haramayn” or “haremân” meaning two sacred territories.” Curiously exhibited at the National Visual Arts Gallery and not at the more prestigious Islamic Arts Museum, these historical captures are taken from the collection of Ömer Fahrettin Türkkan, an Ottoman commander and former governor of Madina. Astonishingly modern and beautifully shot, curator Mohamad Majidi Amir rightfully states, that “…a range of photographic techniques were seemingly used in an effective and scrupulous manner.”

|

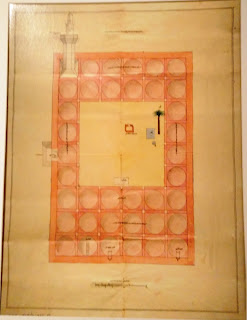

| Plan of Masjid Quba |

An incredible panorama of Makka greets the visitor, where a mountainous terrain surrounds a city with a grand square, the majestic Ajyad Fortress still standing as the watchtower. Photographs of al-Ḥarām al-Sharif display a good variety – the square is filled with a faithful congregation during prayers, empty when renovation works are carried out, and there is even one snapshot of the Ka’aba immersed in water during a 1910 flood. In contrast, pictures of Madina denote a more fortified and spread out area. Memorable architectural features include gleaming domes at Baqi’ cemetery, and the beautiful cloister of al-Masjid an-Nabawi. Exhibited also are hand-drawn building plans that often display a practical sensibility, where the oft-centre palm tree or minaret helps to dispel the oversimplified notion of beauty and symmetry in Islamic art.

|

| Makka al-Mukarrama and al-Masjid al- Ḥarām (1879-1880) |

Many onion-shaped domes populate these pictures, and wall notes consistently remind of structures now demolished in the name of development. The laying of train tracks and road expansion works are shown, where dynamite smoke in one photograph triggers an uncomfortable association with a re(li)gion still embroiled in armed conflict. Saudi Arabia, the nation where these two sacred territories are located, also has one of the world's highest military expenditures. Its influence as the number one oil-producing country is unparalleled, evidenced from the timid international response to the recent crane collapse disaster at the Masjid al-Ḥarām, which claimed too Malaysian lives. These selection of Haremeyn photographs contributed by an Istanbul-based cultural institute, then become a useful counterpoint, at visualising holy sites during a pre-Saudi era. Was it holier then?

|

| Masjid Quba Road (1916-1918) |

“Thus have We made of you an Ummah justly balanced that ye might be witnesses over the nations and the Apostle a witness over yourselves; and We appointed the Qiblah to which thou wast used only to test those who followed the Apostle from those who would turn on their heels (from the faith). Indeed it was (a change) momentous except to those guided by Allah. And never would Allah make your faith of no effect. For Allah is to all people most surely full of kindness Most Merciful. We see the turning of thy face (for guidance) to the heavens; now shall We turn thee to a Qiblah that shall please thee. Turn then thy face in the direction of the Sacred Mosque; wherever ye are turn your faces in that direction. The people of the book know well that that is the truth from their Lord nor is Allah unmindful of what they do.”

- The Qur'an 2:144–145 (trans. Yusuf Ali)