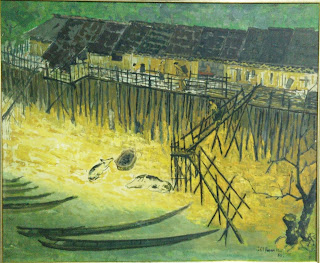

...In contrast with Georgette’s luscious paintings, Lai Foong Moi’s works lack the former’s decorative flourish. Adhering to traditional composition conventions, landscapes such as ‘Menuai Padi’ have a high horizon line with a diminishing scale of figures. Pictures done in 1959 of an Iban dancer and a Dayak longhouse intrigue for its early depictions in Borneo, as I succumb to a heroic imagining of one Seremban-born 30-year old unmarried female artist crossing the sea to visit tribes located on a neighbouring island. Perhaps paying tribute to celibate womenfolk brought into Singapore as construction labourers, ‘Samsui Woman’ displays a more controlled brushwork. The artist skilfully presents the sitter as an iconic figure, despite her hunched back and stout limbs, complete with receding hills in the background.

|

| Lai Foong Moi - Rumah Panjang Dayak (1959) |

Next, four intimate works by Chen Jen Hao grab attention. Maroon rambutans hang within a Chinese scroll. One stern-looking young person seats cross-legged and is holding a book, the portrait’s outline highlighted with turquoise pastels. A well-built man sleeps on his side with arms extended, the fleshy thigh at the picture’s corner potentially mistaken for a photographer’s fingers caught in the frozen frame. Fishermen mend nets underneath a canopy facing the sea, a mountain visible on the high horizon line where sea and land meet. Having read about the queer narrative in Patrick Ng’s batik paintings earlier in the day, I circle back to Jen Hao’s topless men done also in the 1960s. The tender image of a sleeping man is a rousing one, and the cropping-off adds to the picture's enigma.

|

| Chen Jen Hao - After A Hard Day (1963) |

Head portraits done in wartime Muar by Liu Kang present faces with determined looks, which describe a socialist idealism popular at that time. Walking past works by Yeo Hoe Koon and Lu Chon Min, I suspend my presumptions of a useful connection between France and these exhibits, besides the factual references to art schools. Mid-20th century French art is associated with the Art Brut and Nouveau Réalisme movements, which are not represented here. Long Thien Shih writes for the 1991 “A Touch of French” exhibition, “(n)ow, a common trait among the Paris-trained Malaysian and Singaporean artists who are Mandarin literate is their “delayed” reaction to the Modernist Movement, a 20 years delayed reaction.” Moving onto abstract prints by Latiff Mohidin, this statement still unfortunately applies to much Malaysian art now.

|

| Ponirin Amin - Di Pentas Mu yang Sepi (1979) |

Ponirin Amin’s square grids denote many things – a functional connection, an aesthetic symmetry, a picture plane – even a political position, as in the multi-planar arrangement for ‘Alibi Catur di Pulau Bidong’. Powerful lines and catchy titles (‘→ !!!.....’ and ‘3 Sequences’) by Abdul Mansoor Ibrahim captivate, while Juhari Said’s ‘Baju Kurung, Petaling Street, Bombay dan New York’ evoke faraway spaces embedded within the linocut flower patterns. Hung beside are yummy mangosteens by Lim Kim Hai, and three intriguing works by Chew Kiat Lim. The latter’s batik creations project a sinister feel via surreal juxtapositions, while green hues and distinct shading in ‘Pembebasan’ transform a typical Nanyang subject matter into a tinted illusion. Rounding off this section is Ng Bee, whose stoic characters, hatched lines, and symbolic objects, present a uniquely attractive art-making approach.

|

| Juhari Said - Baju Kurung, Petaling Street, Bombay dan New York (1993) |

Seeing older works by established artists is a delight, as it offers potential insight into an artist’s evolution. Observable from labels too are the institution’s acquisition trend - questionable taste and all - such as the 12-year gaps that separate three works by Foh Sang, or the 10-year difference in collecting three pieces of from Hoe Koon’s “Bouquet”. Edith Piaf on repeat and a romanticised view of Paris, irritate me to no end; however, any attempt to re-present artworks buried within the national collection is a welcome initiative, in times when society demands transparency in public asset acquisitions. Perhaps, curators can be given the opportunity to put together four-monthly shows “from the collection of BSLN”, instead of a dreary year-long freeze frame of “Recent Acquisitions”. Finding the diamond in the rough, is worth the displeasure of seeing Ken Yang’s paintings again.

|

| Ng Bee - God (2012) |