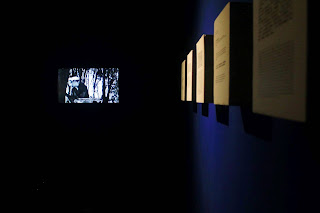

Stepping straight into a narrow space, a screened documentary shows interviews with people of distinctly different ethnic and social backgrounds, telling a story of friends living together on an island called Mengkerang. Excerpts from historical documents (including a ‘prequel’ of

Sejarah Melayu) are printed on wooden boxes lining the corridor, as scenes of a

large rock, tombstones, a flag’s shadow, and children playing football, are glimpsed out of the corner of one’s eye. Only when I read a

bigoted statement made by the former deputy prime minister, that this whole set up falls apart as a sham, ironically triggered by a fact which I am certain was true (as learned from news reports). Truth reveals itself via an audio-visual sensory hierarchy – the memory of a read story, triumphs over a video narrative playing in front of me right now. Gamelan beats ensue.

![]() |

| Installation snapshot of A Day Without Sun in Mengkerang (Chapter 1) 棉佳蘭一日無光 (第一章) (2013) [photo from Au Sow Yee's Facebook page] |

“Perhaps we may re-boost the resistant momentum of images with

the after-image in our consciousness”, writes

Au Sow Yee in describing her works in “The Mengkerang Project”. Exhibited and re-titled as “

Habitation and Elsewhere 居所與他方”, other abstruse terms appear in its catalogue essays, such as

Documentality 纪录性, Utterance of Moving Image 影像的口气, and

The Syntax of Memory 记忆的语法. Looking at the main screen – a compilation of footage from classic Malay films and British Pathé newsreel – ‘Sang Kancil, Hang Tuah, Raja Bersiong,

Bomoh, the Missing Jet and Others’ compounds one’s helpless feeling at the convoluted messages this video installation projects. The voice-over folklore echoes the first exhibit with its multiple narrative threads, but feels further disjointed due to the misalignment between moving picture and sound.

![]() |

| Snapshots of Sang Kancil, Hang Tuah, Raja Bersiong, Bomoh, the Missing Jet and Others (2015) |

Distrust is sowed at this stage, as my pessimistic self can only imagine the invisible migrant worker narrators in ‘Pak Tai Foto’, as voice actors. Songs sung in the individual’s local language are charming, and the relatively slow-moving diptych creates an uncanny feeling of suspended time, which helps re-set the context of this exhibition. The power of spoken word is a formidable one, as it forms mental images quicker than visual association, which supplements the previous realization of how truth manifests within the audio-visual hierarchy in a gallery setting. Despite the symbolic references to the creation of national identity, Sow Yee’s project demands further research (

post-production for the art exhibition viewer?), and its artistic presentation is sufficient to

trigger one’s curiosity to find out more about her source materials.

![]() |

| Installation snapshots of Pak Tai Foto (2015) |

There is no nostalgia – the inside of

Foto Pak Tai is really old. The small lane beside it houses red-lit rooms where migrant workers pay monies in return for sexual pleasure. Video captures in ‘A Day Without Sun in Mengkerang (Chapter One)’ are taken from a road trip, sometimes with an iPhone, hence the eye-level horizons. The original

Hikayat Sang Kancil cartoon lasted only one episode, and was

not aired until five years after its production. Distant tracking shots of a person from behind always invoke suspicion, this camera technique used to film Chin Peng in Baling, a place incidentally also associated with the wonderful legend of Raja Bersiong. Women were trained by the British to fight communists.

The Missing Jet does not refer to MH370. Warrior scenes influenced by

Ben-Hur and special effects (a king transforms into a dragon) in a 1968 Malay film is particularly hilarious.

![]() |

| Snapshots of Sang Kancil, Hang Tuah, Raja Bersiong, Bomoh, the Missing Jet and Others (2015) |

Sow Yee’s method is complex – this challenge perhaps understated due to the perception that video is a contemporary medium – and ambitious. She attempts to exorcise personal questions of identity, while maintaining an academic rigour to track the history of moving images. This disconnect is evident

in the commentaries by

Taiwanesewriters, who are not familiar with the local language and landscapes hence a focus on the immediate output. At FINDARS, Yap Sau Bin compares her project with other Malaysian artists who dwell on the subject of geography and identity, but the

politics of images is a topic not broached. In this contemporary age of appropriation, the emphasis placed upon the image seems outmoded at first, yet Sow Yee’s research-based presentation highlights the subconscious impact of images, a notion worth meditating upon.

Video record of talk by Yap Sau Bin titled "Conversing/Locating/Weaving an Imaginary Non-Landscape (Or Seascape?)", held at FINDARS on 2nd August 2015 (part 1/3) [from Kien Yeo's YouTube channel; Parts 2 & 3 are on Community Arts Projects: Cultural Exchange Operation Facebook page] The artist situates the project firmly within a space-time domain, reminding the audience in her exhibition opening, about “The forgotten? The hidden? The imagined?” Differing narratives do not tell a single truth – à la

Rashomon and its linear storytelling – but the truth lies within an oscillating mediation between then and now. Sing

Song-Yong writes, “…one of the attractions of Mengkerang lies in the separation and out-of-alignment of images and voices as well as the complex sounds, complex tones, and even the heterogeneity of the languages expressed in this work.” Translation is a problem, but it is a delightful problem to tackle, as

Sharon Chin reflects, “…translation is a way to understand something twice (…) It’s like overlaying the same image on top of another, and they don’t quite match (…) Translating images is a way to understand them again and again.”

Video record of exhibition opening talk by Au Sow Yee, held at FINDARS on 2nd August 2015 (part 1/2) [from Kien Yeo's YouTube channel; Part 2 is on Community Arts Projects: Cultural Exchange Operation Facebook page] After a first viewing, I found the best place to stand and appreciate the installations together. At a corner of the gallery, bathed in light and sound emitting from all four screens at once, the excessive stimuli triggering a continuous flow of mental images. The obscure terms start to make sense – memory as syntax, utterance of moving images, documentality… Where do I currently inhabit? I am in an exhibition space of an art activist collective, in an old building near the next major street demonstration, in the capital city of a country embroiled in political corruption, in a region where its people contest identities but seen by the West as the next economic 'tiger', on a blue and green planet (as we are told) amidst a dark solar system. Just like the zoom-out-from-street-level-to solar-system effect seen in Hollywood films. CUT!! NG!

A Day Without Sun in Mengkerang (Chapter 1) 棉佳蘭一日無光 (第一章) (2013) [from Au Sow Yee's Vimeo page]

.bmp)

.bmp)