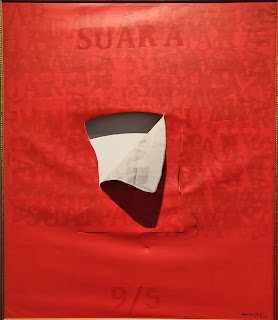

Dominating an exhibition space is one thrilling aspect when appreciating Chong Kim Chiew’s work, and his latest solo show does not disappoint. Visitors are greeted immediately by small bits of litter on the floor, that one may perceive mistakenly as faeces from the gallery owner’s pets. Upon closer inspection, each ‘Pupuk Kandang’ piece constitutes a dismembered finger fused with a piece of dung. Are these sculptures condemning keyboard warriors, and the amplification of fake news on social media? More likely, it is a satirical take on artworks infused with double-bind meanings and interpretations, that grab attention via a violent representation. The work is attributed to a Zaskia Roesli; Are we looking at a stereotypical creation by an Indonesian artist?

|

| Installation snapshot of Zaskia Roesli - Pupuk Kandang (2018) |

The installation-exhibition statement presents the artist’s intent, where as “more international curators cast their attention on the region, presenting its culture within the framework of “Southeast Asia”, Chong questions the validity and authenticity of such projects, but also sincerely wonders whether we can indeed gain insight from outsider perceptions.” Following on his last solo show, personas are created with names conforming to stereotypes of regional artists. Laugh, at one’s own peril. We know that Kim is an American-born Taiwanese – Are Cruz, Aziz, Kuedbut, referring to artists from Filipino, Malay, and Thai descent? The most amusing avatar belongs to its curator Doppelgänger Labor, a literal jab at curators acting as an extraneous burden to artists’ presentations.

|

| Installation snapshot of Liam Smith - We Have Never Change #1 - #4 (2018) |

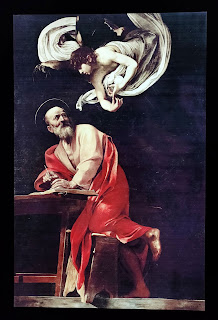

The viewing continues with close-up photographs of mannequins donning Malay headgear, by a Liam Smith – an English resident in Singapore, perhaps? “We Have Never Change” highlights the Caucasian facial features of these dummies, which pictures were shot at the Muzium Kesultanan Melayu Melaka. The portraits collectively pose the obvious question – must presentations of local traditions be supported by a Western framework? Or is there a larger problem, about this question being posed by a Caucasian? Next, one encounters a big inflatable eyeball by a Paithoon Kuedbut, this balloon being one spectacular example about looking – the viewer looking at the artwork, the artist’s creation looking back at the viewer. ‘Paithoon’ translates roughly to cat’s eye in Thai, and points to the metaphysical characteristics inherent in many Thai artists’ works.

|

| Paithoon Kuedbut - Planet (2018) |

Descending from a celestial plane (‘Planet’) to something more grounded (‘Inclined 60 Degree – A Space Within A Space’), an upside-down wooden house follows. Visitors are cramped then forced to bend down, just to walk through this work within the gallery space. The construct recalls recent house-sized installations at the Singapore Biennale, where inaccessible spaces are the focus of a work. Aptly, this makeshift woodshed is labelled Muzium Negara Sementara, thereby proclaiming itself as a piece of contemporary art. Produced by an Emran Aziz – curiously quoted as a Bruneian – one assumes this construct presents a critique about local/regional museums needing a shake-up, in all its different connotations. Or is it about the sideways interpretations of artsy-fartsy subject matters, that lack originality beyond its impressive façade?

|

| Installation snapshot of Emran Aziz - Inclined 60 Degree – A Space Within A Space (2018) |

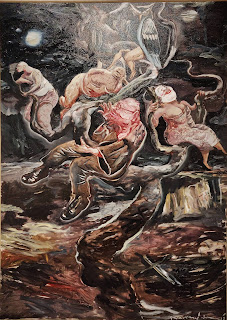

The exhibition culminates behind one wall in ‘The Traversal Landscape’, where a 3-channel projection allows visitors to cross within videos through folds in the hung cloth. The South China Sea is often referred to as the unifying element among Southeast Asian (SEA) countries, and this geographical fact acts as a metaphorical trigger to reflect upon national identities and migratory cultures. A snapshot of Kim’s skin flashes occasionally on the third video, which is a slow-motion take of the second channel, that itself is a reverse playback of the first video. Attributing this work to a Filipino (Alon Vedasto Cruz) seems opportunistic rather than planned, as one’s walkthrough from the gallery entrance to the final projection, presents a narrow-to-general view of “Southeast Asian contemporary art.”

|

| Installation snapshots of Alon Vedasto Cruz and Kim - The Traversal Landscape (2018) |

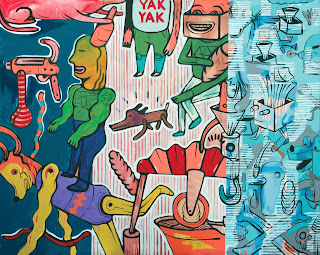

Whimsy is deployed as an approach towards the question on hand – how does artists in this region portray oneself, especially when one is swept along international art trends, by assertive curators and bigwig collectors? Kim Chiew’s exhibition title intimates a half-serious attempt at coming up with a curatorial concept for a museum show, that is as vague as it is absurd. Such jibes at institutional looking and presentation, are exacerbated in the form of plastic sheets that demarcate the gallery space, which literally blur the lines of cultural identity and aesthetic inclinations that characterize the Southeast Asian artist. That this installation is located within a relatively new gallery with regional aspirations, only makes the artist’s critique even more potent. Do not/ go into/ the mist do not/ Go back/ To the dark/ Do/ Not stand/ Still

|

| Snapshot of plastic sheet demarcating the gallery exhibition space |

“Do not go gentle into that good night, Old age should burn and rave at close of day;Rage, rage against the dying of the light.Though wise men at their end know dark is right, Because their words had forked no lightning theyDo not go gentle into that good night.Good men, the last wave by, crying how bright Their frail deeds might have danced in a green bay,Rage, rage against the dying of the light.Wild men who caught and sang the sun in flight, And learn, too late, they grieved it on its way,Do not go gentle into that good night.Grave men, near death, who see with blinding sight Blind eyes could blaze like meteors and be gay,Rage, rage against the dying of the light.And you, my father, there on the sad height, Curse, bless, me now with your fierce tears, I pray.Do not go gentle into that good night. Rage, rage against the dying of the light.”

– Do not go gentle into that good night, Dylan Thomas, In Country Sleep, And Other Poems, 1952

|

| Opening the second layer of 'The Traversal Landscape' to peek into its third layer |