A giant stick figure disposing off its head, greets the visitor into Chong Kim

Chiew’s solo exhibition, where some works are attributed to the artist’s avatars. As if needing a punchline to pull together the

group show, this mural utilises a universal warning sign to grab visual attention, its facile presentation unlike Kim Chiew’s typically less pretty creations. The icon nevertheless exudes the artist's confident charm, here daring the invested viewer to dispose preconceptions, or be blown away by its conceptual heft. Stickers delineate the manifested identities, its author and title (‘0 – Across your space, across his(her) space, across my space.’) constructing pronouns that describe a third dimension, alluding to a painterly issue confronted by artists for a long time. In Kim Chiew’s creations,

time is presented as the third trajectory which alters spatial experience.

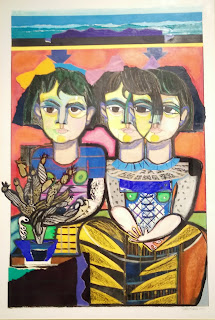

![]() |

| Installation view: (2015) [from l to r] Kim – Skin Time; 0 – Across your space, across his(her) space, across my space.; Topy – Exhibition Logo Design No. 1 |

Stating this approach in a direct and literal manner is ‘Skin Time’, an 8-hour slide show composed of 1-minute close-up stills of digital-format time inscribed onto human skin. Juxtaposing one’s biological clock with calculated running numbers, the projection was eleven minutes slower than universal time during my visit, which further highlighted one’s difficulty in experiencing time. This work is attributed to the avatar named Kim, “…an Asian who stays in USA…” who is probably a reference to Taiwanese artist Hsieh Tehching. While the latter’s performances are endurance feats that mark the human condition as art, Kim’s ‘Skin Time’ compacts the notion of time’s passing into a factor for gallery art appreciation. A suggestion to stretch the work’s concept further: price the video in accordance to one’s visiting time/ decision to buy/ MYR vs USD exchange rate on-the-day, etc.

![]() |

| Installation view of Chong Kim Chiew – Boundary Fluidity (2014 –ongoing) |

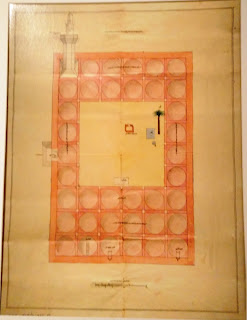

Displayed in the next section are the papier mâché bricks of

‘Unreadable Wall’, rendered impotent when stacked up against a non-functioning revolving door. Doubling back to the main exhibition – “Boundary Fluidity” – eight tarpaulin canvases hang majestically from the ceiling, while a couple remain rolled up and leaned against the wall. One piece is laid out on the ground, shimmering like waves underneath the fluorescent lights. Ink and paint cover the polytarp surfaces, a number which underlying black and orange layers are exposed via cutting or peeling. Historical map lines are traced and overlapped, place names are written and erased, resulting in mostly ineligible markings. In a video last

seen at Lostgens’, these individual tarpaulins are placed in isolated environments (beach, car park, road, etc.) in various physical states. Folded, immersed, covered, washed up…

![]() |

| Installation view of Chong Kim Chiew – Boundary Fluidity (2014 –ongoing) |

Kim Chiew’s photocopied jottings stuck to the wall present clues to these obscure images. One A4 sheet circles Chinese characters that spell out inhibited and exhibited physical states, these words describing also emotions and actions in the Mandarin language. Sketches featuring old works associate material and colour, with dynamic gestures and static surfaces. By questioning the legibility of maps and mapping, the artist addresses the painterly issues of 3-dimensional representation on a flat canvas, also imbuing his works with the idea that time factors into depicting/ deciphering reality. History is a slippery notion and the future is unpredictable, yet the typical individual expends much effort to understand and relate the present to these two dimensions. Identity is a fluid construct, and the projection of time becomes the boundary.

![]() |

| Photocopied sketches and jottings by Chong Kim Chiew |

These tarpaulin works have enough substance to stand

(hang/ lie/ lean/ unfold, etc.) alone within a solo show, but creations by Kim Chiew’s avatars serve to distract then extend the conceptual limits of art making and exhibiting. Framed photographs of a spot of chipped paint, a wall socket, and the floor edge, intend to state the illusionary conceit of representations. But compared to its last

arrangement at G13, or the stickers of wall cracks and door knobs

stuck within Galeri Petronas two years ago, this intervention appears too passive and regressive. Hung nearby for good measure is ‘White Over White, Black Over Black-Map’. Pixelated squares depict a blown-up image of rolling waves, thus transforming this

2011 work into a metaphor within the show’s context. You stand on the coast, but look too hard and you may be sucked into the whirlpool’s centre. Be careful!

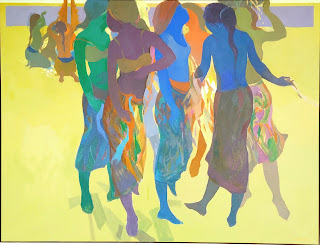

![]() |

| Installation view of Chong Kim Chiew – Boundary Fluidity (2014 –ongoing) |

This show is not aesthetically pleasing, but the gravitas of its exhibited objects makes up for this deficiency. Tracing military trails and land formations on 8 by 6 feet polytarp obfuscates the viewer, then leads one away from the canvas. This counter-intuitive response to an artwork is demanded by the ambitious artist, in his persistent reference to the “third space”. By presenting the illusion of slow-moving flux, the artwork is never finished, the truth is never absolute. Persistent looking, thinking, and re-looking, is encouraged, thus cultivating an appreciation of visual objects where a narrative always shifts, and its focus warrants regular reconfigurations. Time passes. Questioning the ego in the act of seeing is perhaps nihilistic, but the pleasures gleaned from the reflective impulse of looking, is a truly thrilling one.

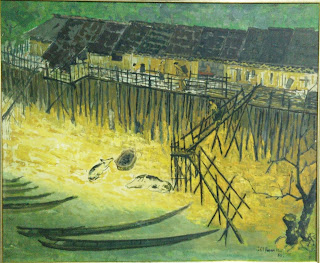

![]() |

| Installation view of Chong Kim Chiew – Boundary Fluidity (2014 –ongoing) |

“Continual transition forbids us to speak of "individuals," etc; the "number" of beings is itself in flux. We would know nothing of time and motion if we did not, in a coarse fashion, believe we see what is at "rest" beside what is in motion. The same applies to cause and effect, and without the erroneous conception of "empty space" we should certainly not have acquired the conception of space. The principle of identity has behind it the "apparent fact" of things that are the same. A world in a state of becoming could not, in a strict sense, be "comprehended" or "known"; only to the extent that the "comprehending" and "knowing" intellect encounters a coarse, already-created world, fabricated out of mere appearances but become firm to the extent that this kind of appearance has preserved life--only to this extent is there anything like "knowledge"; i.e., a measuring of earlier and later errors by one another.”

– The Will to Power, Friedrich Nietzsche, s. 520 (1885) [translated by W. Kaufmann. 1968]

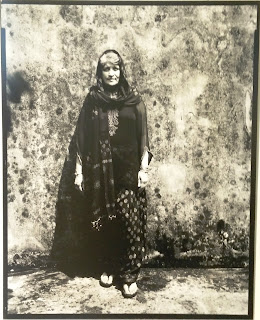

![]() |

| Mobile snapshot of Chong Kim Chiew – Skin Time (2015) by Sharon Chin, as published on 21st October 2015 in Notes on “Be Careful Or You May Become The Centre” at sharonchin.com |