Pushing open the gallery door, one is greeted by a toy panda souvenir encased in a suspended acrylic cube. It hangs in the balance, affixed to one bottle of

1Malaysia mineral water placed on the floor, an accident waiting to happen. Flanking the visitor, blue light illuminates a blurred image of one voter’s cross and the ideogram 票 (vote/ ticket), creating a spooky suspicion that Malaysian political symbols have taken on a life of its own, then

occupied this Brickfields shop lot. Sidestepping divider screens made from a single black & white photograph composing many sheets, I see limp plastic car banners rolled up in one corner, before getting overwhelmed by a line of lovely pillow covers hanging overhead like flags.

![]() |

| Installation snapshot of entrance into After Image: Living with the Ghosts in my House at Wei-Ling Gallery: [foreground] A Chinese Vote (2015); [right] Vote and Vow (2015) |

Utilising campaign paraphernalia collected from the last General Elections, Minstrel Kuik “…experimented with the idea of domestication – to feminise, to soften the once exuberant, masculine and heroic object. Flags were kept immobile by being folded and sewn, whereas the political iconography of the object is muted by the abstraction of form.” Appreciating the pleats in ‘Flirting with the Moon’, and the folded & puffy flags of ‘A Lonely Star’ (formerly ‘A Thorny Sky’), one can neither discount nor dismiss the original materials despite its alteration. The artist transforms 2-dimensional signs into 3-dimensional symbols, effectively reconciling political symbolism with her contemporary beliefs. Time dilutes the image, but we are reminded not to forget.

![]() |

| A Break 1 (2015) |

Such apparitions manifest in an 11-metre long braid made from blue flags with plastic clappers fixed to its ends. Suspended in a manner that outlines the roof of an altar, ‘Ghost in the House’ functions as a barricade to hopeful memories, as it employs a motif – the braid – that Minstrel used in previous works as a symbol of the past. Tiny circular photographs show yellow-clad protestors and ‘A Worm Turns’, like peep holes in a derelict mansion. Lying behind another divider screen are folded-in flags placed on a built-in shelf. Fluorescent lights emit a seedy glow, as political allegiances and tinted biases are transmogrified into morally dubious physical states. The haunted feeling is further exacerbated, as a light box shows one motorcycle rider appearing twice in the same snapshot.

![]() |

| Installation snapshot of Ghost in the House (2016) |

As if setting up for an exorcism rite, two pedestals are erected with folded clothes and a bucket of propaganda materials placed upon it. Captures of the artist making the exhibited works, are printed on one side of ‘Domesticated Politics’ hanging overhead, the banners acting as oversized talismans. Upstairs, ‘A Wreath for the Ghosted’ is put together from crushed paraphernalia, while two images of one girl sways in the air. Titled “Jangan Tipu”, charcoal drawings present photographic negatives of women staring out at the viewer with white hollowed eyes. Rotating stand fans and creaking floor boards contribute to one’s heightened awareness, which Minstrel again demonstrates her uncanny ability in utilising exhibition spaces. What is there to be afraid of?

![]() |

| Installation snapshots of Domesticated Politics (2016) |

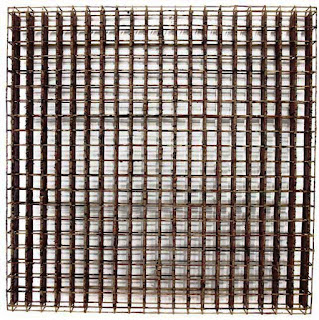

Having seen a number of the exhibits online (from the artist’s last

solo exhibition at Run Amok Gallery),

after-image offers a two-fold reflection. Here, things are seen in a different light, literally. Playing upon the mental associations of colour and form in our collective psyche, one’s current perspective towards local politics is interrogated. Recognising is mistaken for seeing. While abstraction is a visual strategy to invoke unconscious sentiment, re-presenting an existing photograph evokes a time-conscious and more difficult reaction. Personal experience informs and distorts its interpretation, and Minstrel’s grids that back these re-presented images forcefully states the illusion. Has the

hope present at the last

Bersih gathering dissipate?

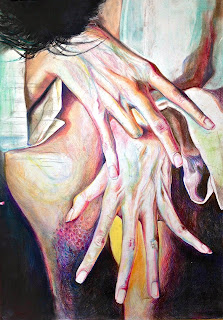

![]() |

| Jangan Tipu 1 (2015) |

The grid is a material background for

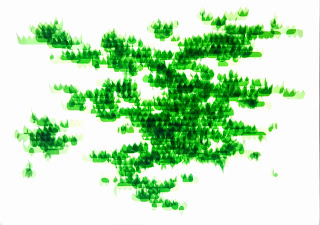

“The Gridded Ghosts”, a row of ten photographs that capture cut-out collages on a paper mat. Propaganda is streamlined into templates, politicians are reduced to faceless bodies and gesturing motions, and stationary becomes part of the composed forms. These delightful images invoke direct responses – Who is this? What does the newspaper headline say? Which party? It is farcical to ponder such questions, yet Minstrel’s compositions are always attractive enough to warrant more than a glance. Looking at the green monotone in ‘Papa’, or the colourful pleated fans in ‘Mother’, it becomes evident that such visual cues are embedded into the Malaysian collective psyche. How do we progress, if political presentations cannot?

![]() |

| From "The Gridded Ghosts" (2016) - [l] Mother; [r] Papa |

We cannot, because the ghost is still in the house. ‘Old Wave’, a large print of cockle shells laid over pictures of delegates’ gathering from a single-race political party, is lit red and hangs menacingly in one corner on the ground floor. Ultimately, our political situation is not an experiment about optical illusion… Loaded metaphors and compositional skill can easily be read into Minstrel’s creations, but it is the play on identity politics and time that define this exhibition. Found objects and a home setting clearly manifest in her works, the artist thereby relating herself as a common citizen, protesting against a hopeless situation the only way she can. I high-five one plastic hand before leaving the gallery, as the after-images of this exhibition begin swimming in my mind.

![]() |

| Old Wave (2015) |